This story is co-published with Indian Country Today and is part of The Human Cost of Conservation, a Grist series on Indigenous rights and protected areas.

The rivers that run through the steep valleys and rocky cliffs of the Laponian Area are fed by crystalline alpine lakes and glacial streams. Many of the forests that tower over the land have stood for more than 700 years and teem with wildlife. In the spring and summer, when the midnight sun traces wide circles across the bright blue sky, crowberries blanket the meadows and yellow globe flowers dot the snow-capped peaks.

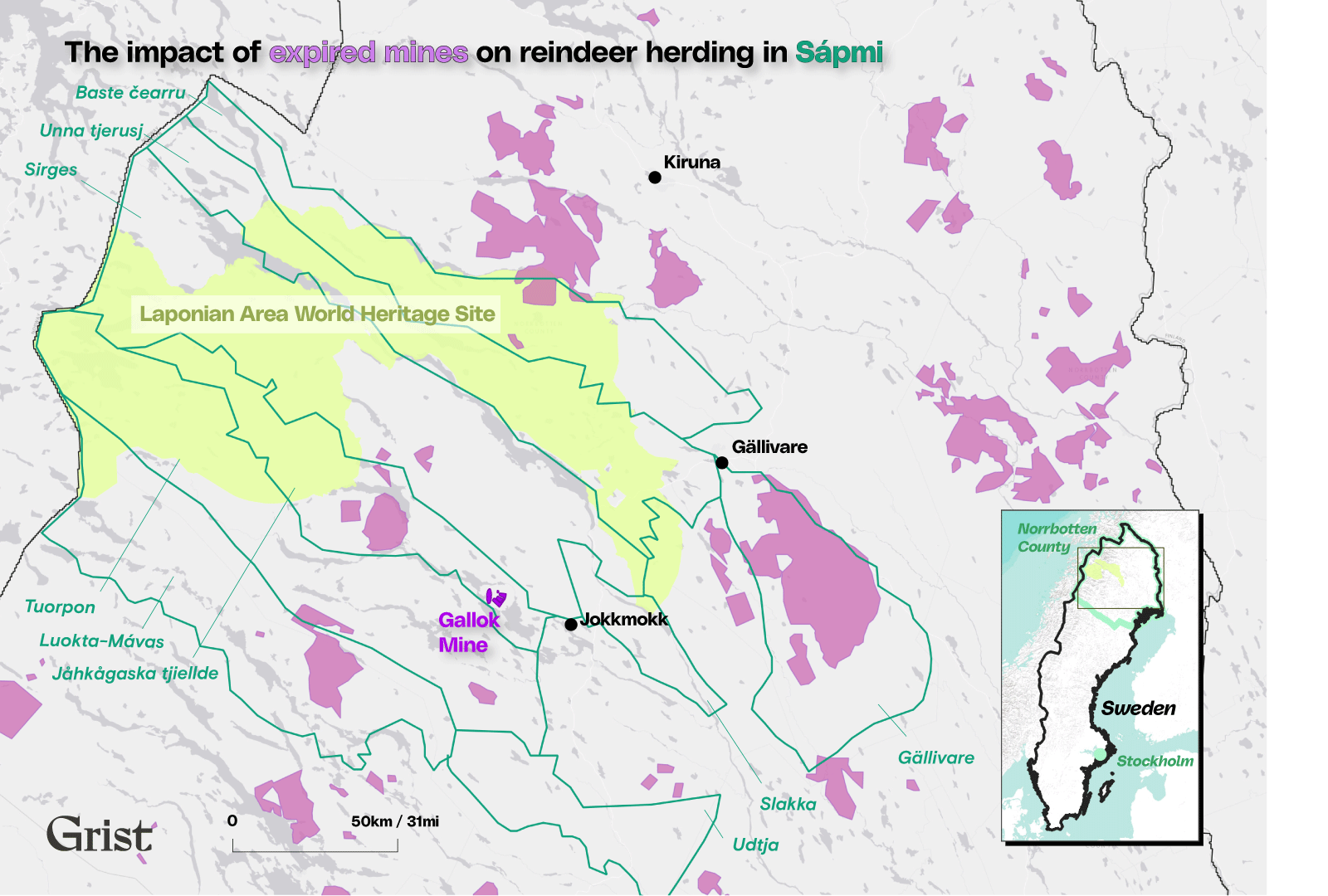

In those warm months, this region in the far north of Sweden provides a bounty for large migrating herds of reindeer: grass, birch, and herbs. Snow patches in the high mountains provide relief from insects on hot days, and the verdant lowland provides ample grazing as the nights cool. When winter arrives, rivers and marshes ice over, and the reindeer venture south beyond the Laponian Area along well-worn pathways, traveled by generations of Sámi reindeer herders, to winter grazing lands. This migration of both the reindeer and the Sámi who tend to them, reveals an ancient relationship with the land that persists to this day.

“It is the variation of landscape that makes the area so good,” said Helena Omma, who is Sámi and president of the Association of World Reindeer Herders. “Reindeer use all these landscapes during different times and conditions.”

Nestled deep in the heart of Sápmi, the traditional homelands of the Sámi, the Laponian Area covers nearly 4,000 square miles. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, considers it a place of “exceptional beauty” and its stewardship by Sámi hunters, fishers, and herders “an outstanding example” of traditional land use. That combination of natural and Indigenous values was essential in the agency’s decision to declare it a World Heritage Site.

Since earning that designation in 1996, Sámi leaders and the Swedish government have, for the most part, enjoyed a successful and cooperative relationship managing the area. But an iron mine, recently approved on land barely 20 miles south of the Laponian Area’s border, is straining that collaboration. If the British-owned Kallak mine is built, it will impede the migration of reindeer to critical winter grazing lands and sever routes Sámi families and villages have relied upon for centuries.

“We need the lands outside of Laponia to ensure that the Sámi culture within Laponia can survive,” said Omma, who is also co-chair of the Laponiatjuottjudus Association, the administrative body that oversees the World Heritage Site. “We want to protect the land because the reindeer need the land, and we need the land.”

To protect the Laponian Area, their culture, and their livelihoods, Sámi leaders say Sweden must stop the mine. By threatening their way of life, they argue, the mine threatens the Laponian Area’s status as a UNESCO site.

These tensions highlight growing international concerns about UNESCO’s treatment and inclusion of Indigenous communities in establishing and managing World Heritage Sites. Although this occurs around the world, it is perhaps most explicit in Thailand and Tanzania, where violent evictions and killings define relations between Indigenous peoples, governments, and the U.N. agency’s reputation.

The issue, which has unfolded over decades, could grow more widespread. World Heritage Sites, which are protected by the United Nations, are rich with biodiversity, making them a small, but essential, part of the successful implementation of the global conservation program 30×30. That ambitious effort calls for setting aside 30 percent of the world’s land and sea for permanent protection against development by 2030. Given that Indigenous territories comprise almost 20 percent of Earth’s land and shelter almost 80 percent of its remaining biodiversity, human rights experts worry that a history of systemic mistreatment of Indigenous peoples coupled with so rapid a timeline could be detrimental — even deadly — if it does not specifically include and respect those communities and their knowledge.

“UNESCO cannot turn away from its obligations,” said Lola García-Alix, senior adviser on global governance at the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, or IWGIA, a human rights advocacy organization. “States can, but not UNESCO, and we should not allow it to do so.”

When Sweden sought World Heritage Site status for the Laponian Area, its application was based solely on the region’s natural beauty. UNESCO rejected that application, saying Laponia’s splendor was not unique enough to warrant protection. However, the committee said the inclusion of its cultural values in a subsequent application could reopen the process. The country followed that guidance, and in 1996, with essential help from Sámi reindeer herders, secured the land’s protection. It remains just one of a few World Heritage Sites with an internationally recognized connection to living Indigenous cultures, effectively making the Sámi true stakeholders with authority over its management.

The Laponian Area is one of the 1,157 World Heritage Sites worldwide. The U.N. established UNESCO in 1959 after Egypt proposed building a dam that would flood the valley containing the Abu Simbel temples and other antiquities. The campaign saved those treasures, leading to similar efforts in Italy, Pakistan, and Indonesia. Today, 167 countries have at least one place on the list, ranging from iconic locales like the Taj Mahal and Chichen-Itza to smaller gems like the Madriu-Perafita-Claror Valley in Andorra, which provides, in the words of UNESCO, “a microcosmic perspective of the way people have harvested the resources of the high Pyrenees over millennia.”

Such a designation often brings a boom in tourism. Worldwide, these sites attract some 8 billion visitors per year and generate as much as $850 billion in revenue. But the infrastructure needed to handle those tourists often strains the very places and ecosystems UNESCO hopes to protect. Angkor Wat, which was designated a World Heritage Site in 1992, in Cambodia, for example, saw tourism increase 300 percent between 2004 and 2014 alone. Beyond the on-site human impact, places like the Great Barrier Reef, near Australia, and the city of Venice, Italy, face mounting threats from climate change.

Yet many of these cherished places could prove essential to the planet’s survival. The International Union for Conservation of Nature, which advises UNESCO, estimates that two-thirds of natural World Heritage Sites are crucial sources of water, while those in tropical regions store nearly 6 billion tons of carbon. These locations make up more than 1 million square miles of protected terrain and represent approximately 8 percent of all protected areas worldwide. However, only 48 percent of them are considered by the Union to have effective protection and management while nearly 12 percent raise serious concern.

Sámi communities tended the Laponian Area centuries before the Kingdom of Sweden in 1532. That kind of history is not uncommon across the UNESCO system; many World Heritage Sites are near, or overlap, traditional Indigenous territories. What is uncommon is how it has been managed.

It took more than a decade after its inscription as a World Heritage Site to establish Laponia’s oversight board, Laponiatjuottjudus. “It started when I was a child, in ’96, ” said Omma. “It was a 15-year-long struggle where the Sámi’s really worked hard to get a majority on the board, to create consensus-based decision-making processes, and to get reindeer herding rights respected within the Laponia site. It was a long, long struggle against authorities.”

Today, Laponiatjuottjudus is legally responsible for managing the entire region. Representatives of nine Sámi villages work with local and county officials and the national Environmental Protection Agency to manage and maintain the area. Decision-making is grounded in Sámi cultural values and the collaboration has been so successful that the U.N. special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples lauded the relationship.

JONATHAN NACKSTRAND / AFP via Getty Images

But Indigenous peoples worldwide have long raised concerns about violations of their rights within UNESCO sites. Three U.N. special rapporteurs on the rights of Indigenous peoples — independent human rights experts appointed by the U.N. Commission on Human Rights — have reported recurring problems at World Heritage Sites, including a lack of Indigenous participation in the nomination, declaration, and management process of sites; significant restrictions on access to resources and sacred sites; and harassment, criminalization, violence, and killings of Indigenous peoples.

As a United Nations agency, UNESCO must comply with international obligations, including the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Traditionally, the challenge has been doing so in countries where the government regularly mistreats, or even refuses to recognize, Indigenous peoples and declarations of their rights. The United Nations has no punitive tools for dealing with such cases, and UNESCO can only threaten to delist a site — something that has happened only twice in the last 50 years, and never as retribution for human rights violations.

Putting aside that serious shortcoming, UNESCO fails to consider Indigenous communities in even the most fundamental tasks, like telling people the land they’ve lived on for centuries is slated for conservation.

“Many Indigenous peoples are not aware that there will be a World Heritage Site perhaps until they are in a World Heritage Site,” said García-Alix of the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. “They have never been informed. Information is not publicly available.”

Currently, 186 proposed World Heritage Sites are pending review, and although UNESCO’s website states that fact, it offers no details about how they are considered. Evidence suggests the process is increasingly politicized. One study found that political or economic factors played heavily in cases in which the World Heritage Committee ignored recommendations that it decline designation or defer a decision pending additional information.

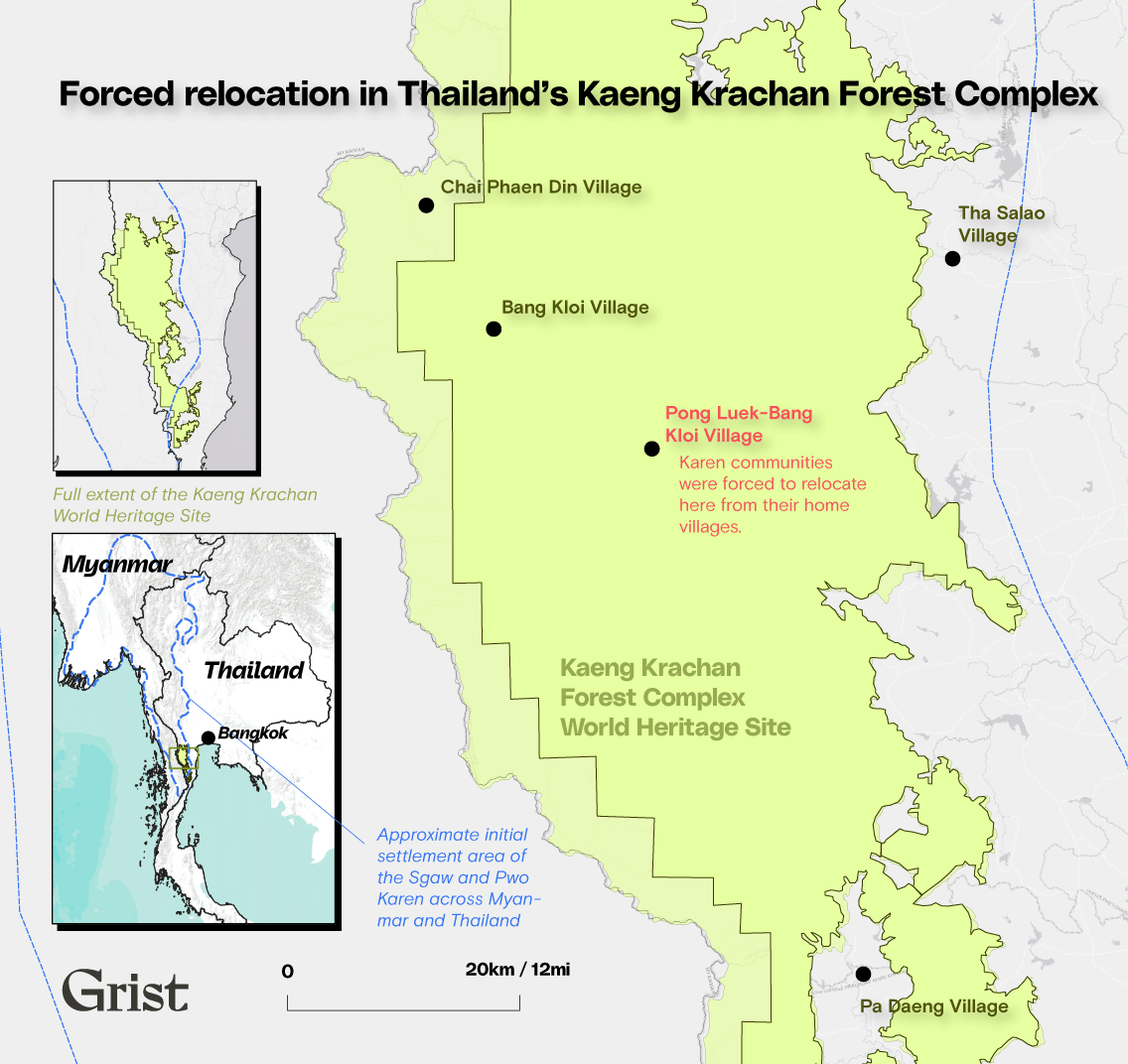

In other cases, the body seemingly overlooks any consideration of the communities impacted by its decision. Such was the case in 2021, when the World Heritage Committee ignored reports of human rights violations in Thailand’s Kaeng Krachan Forest Complex, and inscribed it to the World Heritage List despite pleas from the Indigenous Karen communities within the park, a U.N. human rights panel, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature to defer the nomination.

“Kaeng Krachan is a stain on the whole U.N. system,” said García-Alix. “It raises questions about the accountability of UNESCO as a U.N. organization.”

The Karen have for hundreds of years lived as gatherers and farmers in what is now known as the Kaeng Krachan Forest. In 1981, the Thai government named the area a national park and began relocating the Karen communities from the upper Bangkloy to the Pong Luik-Bang Kloy in 1996. In exchange for voluntarily leaving their traditional homeland, they would receive land to farm and financial support.

Many of them agreed, but upon arriving at their new homes, some families found only sandy, rocky land unfit for farming. What’s more, the support the Thai government promised never arrived, or very little did. The Karen immediately demanded authorities follow through on their promises. When good land and support failed to materialize, communities faced two options: return home or migrate to towns looking for jobs.

Wang Teng / Xinhua via Getty Images

“When we talk with the Karen people who live there, they say that they are not against the World Heritage Site, but their concerns and issues need to be resolved,” said Kittisak Rattanakrajangsri, who is Mien and chairs the Council of Indigenous Peoples in Thailand. “The land issues remain. That’s why they decided to go back to their homelands again.”

The Karen have tried to return home at least three times. Each time, Thai authorities responded with violence, harassment, and forced evictions. Park officials have burned homes and rice barns, confiscated ceremonial items, seized fishing nets, and arrested Indigenous residents and activists.

Timeline of the Kaeng Krachan Forest Complex

At least two human rights defenders have been killed. Tatkamol Ob-om, who was helping the Karen report illegal logging and human rights abuses, was shot by an unknown assassin in 2011. Three years later park officers arrested Por La Jee “Billy” Rakchongcharoen, who assisted affected villagers to file a legal complaint against park officials over the destruction of Karen housing. He vanished until 2019, when Thailand’s Department of Special Investigation identified his remains after discovering a burnt skull fragment in an oil barrel at the bottom of a reservoir. This had no impact on the World Heritage Committee’s decision to add the site to the list.

Rattanakrajangsri says there will be a review of the site’s World Heritage status every five years. “If the independent study shows that the situation is not getting better, and on the contrary, is getting worse, I think that it sends a strong message to UNESCO and other conservation agencies,” he said.

Such abuses, and what appears to be a history of indifference to them, go back decades. The Maasai of Tanzania have faced repeated violent evictions from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, a UNESCO site since 1979. The Maasai, mobile pastoralists much like the Sámi, have moved through the region for centuries, and although UNESCO has insisted that it never called on Tanzanian authorities to expel them from the park, it has done little to address the tens of thousands of Maasai who have been forced from their homelands, injured, and even shot and killed. In the last year alone, nine U.N. human rights experts and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature have called on Tanzanian officials to halt relocation until consulting with the Maasai. Human rights defenders have demanded UNESCO sever ties with the Tanzanian government.

“The World Heritage Committee is closely monitoring the state of conservation of the mentioned properties,” said a spokesperson for the World Heritage Centre. “Including the issues related to the rights of the Indigenous peoples.”

The agency could begin to address such injustices by establishing a mechanism under which Indigenous peoples and human rights watchdogs could bring evidence of violations to its attention, said Nicolás Süssmann, conservation and Indigenous peoples project director with Project Expedite Justice, a human rights organization. He also says UNESCO could be more open and clear in its handling of human rights complaints.

“The consequences cannot just be removing or firing an eco-guard who conducted an operation,” he said. “This is not a problem of rogue eco-guards. This is a problem with a conservation model that is incompatible with Indigenous peoples.”

But that conservation model has been the global standard for more than a century, and with more than 100 countries expressing support for 30×30, Süssmann and other human rights experts say the situation will get worse. “You can say you respect Indigenous peoples,” said Süssmann, “but when you have a deadline and you’re used to doing things without Indigenous peoples’ real, and meaningful, involvement, you’re not going to change the way you do things if you don’t have to.”

Süssman says this is especially true when you read the fine print: Under 30×30, countries don’t have to preserve 30 percent of their own lands and waters by 2030. The plan calls only for preserving 30 percent of the world’s land and waters by then. “Nobody is going to demolish a couple of buildings near Central Park to make it bigger,” said Süssmann. “They’re going to get that 30 percent from other parts of the world.”

Much of that land will, almost inevitably, encompass Indigenous territories, which make up nearly a quarter of the planet. In 2016, human rights experts estimated that 50 percent of protected areas worldwide encompassed traditional Indigenous lands covering more than 6 million square miles. Today, protected areas comprise nearly 9 million square miles – an area roughly the size of China, India, Mongolia, and the United States combined. To reach 30{7bfcd0aebedba9ec56d5615176ab7cebc5409dfb82345290162ba6c44abf8bc8} by 2030, more than 15 million square miles must be protected – an area nearly the size of Russia.

All told, protected areas represent just 16 percent of the Earth’s surface, and while there is no disagreement that safeguarding biodiversity is critical to planetary survival, advocates say failing to make human rights foundational to global conservation efforts may continue to drive evictions, violence, and killings in Indigenous territories.

“World Heritage Sites, which are U.N. protected areas, at the minimum, should be the ones who respect and protect Indigenous people’s rights,” said García-Alix. “If I have to be diplomatic: UNESCO has a lack of sensitivity about human rights issues, particularly when it comes to World Heritage.”

Beyond ensuring Indigenous rights and traditional knowledge are respected, such arrangements could advance UNESCO’s preservation goals and help mitigate the impacts of climate change.

A rapidly expanding body of science shows that working with Indigenous communities can accelerate conservation efforts. Legal recognition of Indigenous territories in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest have led to increased reforestation. Studies show that the world’s healthiest forests often stand on protected Indigenous lands, and sustainable pastoralism, like that of Maasai or Sámi herders, offers benefits ranging from preserving soil fertility to maximizing genetic diversity. Formal recognition of territory and rights also creates legal pathways to stopping the development of extractive industries: Indigenous resistance to fossil fuel projects in North America is thought to have stopped or delayed the creation of greenhouse gas pollution equivalent to at least 25 percent of annual U.S. and Canadian emissions. That resistance, however, is often criminalized by state authorities.

Humans have shaped and sustained landscapes for more than 12,000 years, and Indigenous communities continue to care for the territories that have sustained them for generations. Embracing and applying that knowledge – and the understanding that Earth is an interconnected system of physical, biological, cultural, and spiritual networks that extend beyond borders — could go a long way toward addressing the climate crisis. In some cases, like the Kallak iron mine, it even means the difference between life and death.

“We know how this will affect our culture and our livelihoods,” said Omma. “But it’s very common that our knowledge is viewed as opinions, not as knowledge.”

Human rights experts continue to urge Sweden to stop the project, and the World Heritage Centre says a report on its potential impacts will be presented to the World Heritage Committee at its annual conference this September. The committee will then offer recommendations to the Swedish government. For the Sámi, there can be one way forward.

“You can’t coexist with a mine,” said Omma. “It’s not possible.”

But to Indigenous communities like the Sámi, the issue is so much bigger than one mine. Truly protecting a place goes beyond preserving its landscapes and historic sites. It must include the protection, respect, and participation of the people who have, for millennia, lived in good relation with that land and know, perhaps better than anyone, how to protect it for future generations.

“Protection of land is good,” said Helena Omma, “if Indigenous peoples are part of that protection.”